The “Half of All Workers Don't Pay Taxes” Mantra is Starting to Get Taxing

Friday, May 25th, 2012

One of my concerns over the past year or so is the continued use of the phrase “half of all workers don't pay taxes.” It's one of those ideas that needs some context, and it's probably not the kind of context you've read about anywhere else.

The most important part of the discussion is that these are federal taxes. From that perspective only, the statement is true because it is based on publicly available IRS data about the federal income tax. Many workers and others do not pay income taxes. Workers who do not earn enough money to surpass the basic exemptions and deductions are an obvious example. There are workers who choose part-time work, many of whom are students, who pay minimal taxes on their earnings for this exact reason. Others may be investors who are living off of savings, such as retired workers who may be drawing down their IRAs and also have tax-free income such as municipal bonds.

But the federal government is not the only taxing authority. Everyone pays something, especially local and state taxes. Think of retired workers whose largest tax may be the property taxes they pay on their homes, and not their income tax. Income tax can be legally bypassed with ease by investing in municipal bonds, or by just drawing down savings that have already been taxed. Yes, people who live off their savings are avoiding taxes. (There are two good charts that show total tax rates at this site; see figures 3 and 4). About 60% of those who do not pay federal income tax pay social security tax (more about this ahead), and the balance are primarily students, and the elderly spending down their savings.

What is more interesting is that there is little recognition by the general public that every person pays the taxes imposed on businesses when they buy any good or service. Even if you rent an apartment, you pay the property taxes of the landlord, because the landlord has to include them in the total costs of running the building. Shop at a store? You're paying the property tax of the store. Go to a doctor? You're paying the employer share of the FICA tax of the nurse and the office manager. (You're also paying their regulatory compliance costs, liability insurance, and numerous other items).

An important article about income and spending appeared in the New York Times about four years ago. “You Are What You Spend” was prepared by W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. It explains how income data are very inadequate in explaining economic behavior, and how spending and income have little to do with each other at certain periods of an individual's economic life. (I've recommended the article many times; it's worth a detailed and thoughtful read, and it is more relevant to today's debate than it was when published in 2008.)

The biggest problem with the “who pays taxes” argument is that it diverts attention from a discussion of the economic opportunity costs of high marginal tax rates, the effects of inflation on production and investment capital, and how they affect future investment decisions of savers and businesspeople. Higher marginal tax rates and expectations of future inflation raise the go/no-go bar for return on investment analyses to very high levels. Therefore, in this kind of environment, only the lowest risk and highest return projects are funded. This drives business investment sentiment to favor projects that increase efficiency rather than projects that foster expansion. There tends to be no return for a few years for expansion projects because it takes time before they can generate positive cash flows and profits. Efficiency projects have almost immediate returns in terms of lower costs. The latter is one reason why the argument, however spurious, that ATMs cause unemployment is so attractive to many people. Unseen are the massive investments in computer networking and communications technology behind the deployment and ongoing maintenance of ATMs. The ease of use of (most) ATMs is on par with an old gumball machine, with little overt indication of the knowledge, technology, creativity, and investment needed to make them so. The public can see the tellers and sense that there are fewer than years ago; it can't see the programmers and the telecom professionals because they're in the back rooms or working at IBM or another provider. Efficiency investments tend to be inward-looking, tweaking past investments or processes to work better, while expansionary investments are outward-looking, have greater risks, create new processes and leverage newer knowledge and/or technology.

The effect of marginal tax rates on taxpayers who already have large of sums of money is minimal. With good accountants, tax attorneys, and financial advisors, higher rates can be avoided, and often are. This diversion of capital does little to stimulate business activity except for those directly involved in constructing and implementing the fully legal avoidance. I believe it creates activities that are economically unproductive in the long run. Thorough knowledge of regulation pays for itself in higher returns. Whole industries are based on tax avoidance as an important product, such as insurance, investment vehicles and legal advisory services. This shifts investable capital (money and people) from production of goods and services to efforts that create returns from that tax avoidance. The money sheltered in this manner will be used eventually, but it is not the same as it being put directly into investments in the production of new goods and services. There are many intermediaries along the way that collect management and transaction fees in the process for marketing the monies as bonds or stocks or loans or in other forms. If the resources were not sheltered in these ways, they would be spent on goods and services more efficiently. The rewards of tax avoidance end up competing with capital investment opportunities. Because the rewards of avoidance are instant and risk free, they crowd out other uses for the money. Because the risk of avoidance strategies is lower, investors are willing to accept lower rates of return than other investments. Apple has learned this lesson well, as noted recently in the New York Times.Apple's extra cash would be better deployed as special dividends or in more new products.

I've enjoyed kidding others over the years when casual talk sometimes leads to discussions about personal investments. Somewhere along the line they say, “and we own some municipal bonds” or some other retirement or college savings plan. I'll ask why they don't just keep them as regular savings and not use those vehicles. “Oh, the tax free returns are much better,” or “w\We're sheltering it from taxes.” Then I ask, “So, tax rates actually do affect people's behavior, don't they!” We're surrounded by tax avoiders; some may live in our very own homes.

The very high marginal tax rates of the 1950s and 1960s were reached by very few workers. At that time, it was easy to circumvent IRS reporting, unlike today. “Bearer bonds” were issued by many entities, including the U.S. Treasury. The income from these bonds would often be free of taxes because holders did not declare the interest on their returns. The bonds were not registered. A recent chat I had with a retired stock broker was informative, and though this is anecdotal, the comments are instructive. Anyone who had a cash business in the 1950s and 1960s was a regular buyer of bearer bonds. Cash would come into their businesses and into their pockets, and then find its way into bearer Treasuries or corporates. That is, until the pervasive use of credit cards, and especially, the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 that eliminated most bearer bonds. Any corporation that issued bearer bonds could not deduct interest paid as an expense, and municipal bearer bonds were taxable to the holder. Only registered bonds were recognized by tax authorities. The last Treasury bearer bond was issued in 1986. The phrase “clipping coupons” referred to a bond's coupon book. One would bring the coupon that was due to the bank and turn it in for cash, with no significant recordkeeping. No more coupons were needed as bonds were registered and held by brokers and banks for their clients, with audit trails back to the IRS.

Also at that time, if no tax money was owed, tax returns did not have to be submitted. Someone whose income was solely from municipal bonds could clip their coupons and never file a return. Because the biggest reason for a big jump in tax brackets might be an event such as selling a business (it still is today, what one consulting friend refers to as a “significant liquidity event”), the tax code allowed income averaging of prior years. This practice was eliminated in 1986 and is now available only to farmers. In those times as well, there were many loopholes and deductions.

The problems with the tax codes and higher marginal rates only began to drag down the economy when tax brackets were not adjusted for inflation, and more people were affected by them. They realized that they had more income but after taxes had less purchasing power. The stagflation of the 1970s brought the issue into sharper focus. Since then marginal rates have come down, there were far fewer deductions and loopholes, and state and local taxe rates have risen significantly. The full tax burden is what matters, not just federal rates. In the 1950s there were few sales taxes. Now 45 states have them. Local and state taxes and fees are almost never reported in tax burden discussions.

As noted earlier, the social security tax is often the only federal tax paid by many low-earning workers. This highly regressive tax is paid on the first dollar earned, and is often higher than the income tax paid by those low-earners. One of the reasons the income tax law has low marginal rates for those workers is to allow for payment of this tax. An equivalent amount is paid by the employer... which is one of the funnier aspects of the law. In actuality, the employer budgets an amount that will not appear in the employee's paycheck, and sends it to the government. It's an illusion that the employer pays this; the money always comes from the output of the worker. At today's rates, it is 7.65% paid by the worker, and 7.65% “paid by the employer.” Together, that's a high tax rate from the first dollar. Back in the 1950s, the total rate was 4%. Today it's 15.3%.

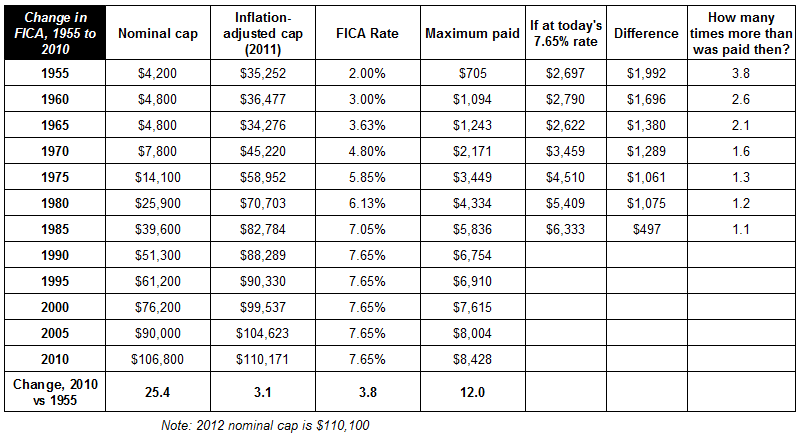

The table below shows how this tax has changed over the years. There has always been a maximum amount of FICA tax collected. When a worker reaches that maximum amount of pay, the tax stops. The table adjusts this amount for inflation. That cap has risen more than 3X since 1955 after adjusting for inflation. At that time, a worker being paid the equivalent of $35,252 in today's dollars would have paid a rate of 2% and a maximum tax of $705. Today, that worker would pay 7.65%, 3.8X what they paid back then, an additional $1,992. For those who have paid the maximum, their total payment has increased by 12X.

As the demands on the Social Security system have increased, the caps have risen to cover more wages and the rates have increased. In today's dollars, a worker could have earned $70,703 in 1980 and have met their full commitment for FICA taxes. Now they would not do that until they earned an additional $40,000.

Ultimately, the “who pays taxes” debate is counterproductive, because it diverts focus on the creation of new capital and new savings. It ignores the life cycle of savings rates and wealth, as young workers have little wealth and older workers have greater wealth almost solely due to the length of time worked, the compounding of older workers savings, and investments in retirement plans. Instead, the arguments assume that all persons are exactly the same, even though their ages and years of work are vastly different. It ignores the regressive nature of local taxes, such as property taxes. It does not recognize the misallocation of capital that tax avoidance, and the encouragement of industries that build upon it, creates. New regulations often create new experts with new avoidance strategies that restrain the full deployment of capital from their natural course.

Since the bulk of investment is made by those who are likely to be in high tax brackets, the risk/reward calculation is affected by the highest marginal rate, assessment of risk, and calculation of future value of returns after inflation. These potential investments are judged on the basis of each additional dollar earned on top of their current income flows.

Inflation combined with taxes is the biggest detriment to expansionary investments because almost all expansionary investments require a period of time where the returns are negative, such as the time spent constructing a building, hiring start-up employees, and developing products, all while generating little or no revenues to pay for them. When tax avoidance has immediate, predictable, and risk-free returns, that crowds out riskier investments that may provide better long-run returns. Removing the rewards for tax avoidance does involve a reduction in marginal rates to create incentives for the production of goods and services. That reduction is particularly distasteful to the political class at this time. The “who pays taxes” debate is about the allocation of old wealth; it promotes inward-looking investments on efficiency and discourages riskier expansionary and forward-looking investments. Until the sentiment and the nature of the debate changes, expect a continued sluggish economic outlook.